Architecture Enforcement in Flutter Apps

When we start writing a Flutter application (or any other language/framework for this matter), we always have an architecture in mind that we want our code to respect and follow. Different architectural styles have different objectives and each buys you different options. However, when the project gets bigger and more coding hands are involved, the code can go astray, and we start diverging from our desired architecture (excluding, the case when the architecture itself shifts as part of an evolutionary design). This phenomenon is known as a model-code gap :

The model code gap is an idea from George Fairbanks’s book “Just Enough Software Architecture.” It describes the conceptual gap between the abstractions we use to discuss software architecture (a model) and the reality of the executed source code. — From The model code gap \ IcePanel Blog

To remediate the model-code gap, we have several tools and techniques that we can use to “Enforce the architecture” (I recommend reading the article as it goes into details about Architecture enforcement). These tools can be summarized from faster and limited, to slower and flexible, as follows:

- Compile time enforcement: This category contains everything that we have in the language that allows us to enforce encapsulation, packaging, and dependency rules and directions. (e.g.: private vs. public fields, package dependencies, etc.).

- Automated checks: This includes extra configuration or extra code that we use specifically to allow/forbid certain things to be done in our codebase. Static code analysis technique is part of this category and in some ecosystems, we can write tests for the architecture of the code by using tools like ArchUnitNET

- Code Review: This involves the human factor, either with pair programming or asynchronous code reviews to “manually” check that the architecture is respected and that the code adheres to the desired design that’s probably has been documented in an Architectural Decision Record.

Theory aside, when it comes to the code, the architecture is not boxes, nor arrows. It’s which parts of the code are together (cohesion) and who is calling it (coupling). So, enforcing the architecture boils down to putting the code in the desired place and allowing it to be called from where we want it to be called. This article tries to go through what we have in our hands as flutter developers to achieve that.

The Flutter case:

Motivation :

Looking at the Flutter ecosystem, most of us (I am a culprit as well) tend to just create a project and start right by putting everything in the lib/ directory, without caring too much about the boundaries of our app, even if we had a specific architecture in mind (like in here and here), we tend to think of it in terms of folders and files which in reality doesn’t have any enforcement at all, and adding a dependency from a folder to another is just a matter of accessing the IDE actions and auto import the missing file which adds the famous import ‘file.dart’ at the start of the file. The ease of such an “import” mechanism is like having a tap that’s ready to be opened, at any time, for free, to add water to the big bull of mud we are forming.

The toolbox :

Flutter, or more concretely, dart, has many mechanisms that we can leverage to enforce our architecture and apply one of the above-mentioned techniques. We will also try to cover the pros/cons of each one, so we can choose the right one for our needs.

For the sake of demo and simplicity, I create a simple/sample app to query a question from the Trivia API.

1. The single file case :

Since Dart provides two access modifiers which are public and library private, then we can use that to control our architecture. The idea is to put all relevant parts of functionality in one file (which is by default one library) and only let the public what we need from our UI, this technique is compile-time enforcement.

You can find the example here.

In our case, we have a QuizzService which is a service that will contain different use cases, for now, it contains only one use case, “Get Random Question”. The only parts that we need public are the service and the Quiz Type. The other ones (like the repository interface and implementations) are all private.

Pros:

- Allow strict control of the public API: only the service and the domain model are exposed.

- Cohesion is very high: since we bundled everything related to the functionality in one file, we have everything together (but this is both a blessing and a curse)

- Simple structure: using the files makes it easier to navigate the project and the folder structure is very flat.

- Fits a package (file, in this case) by feature design.

Cons:

- Maintainability/Readability: Having everything in one file may make it difficult to different code parts and may make the readability of the code suffer. Especially, if the file gets bigger and parts of it (like Database, or HTTP calls) get complicated or very low level. This can be solved by having multiple files with the “library/part/part of” features of Dart that will allow us to create multiple files that are logically equivalent to the same file but these mechanisms are discouraged by the dart team, and they are poorly documented anyway.

- One-way protection: Although we have protected the UI from using the repository directly we don’t have that protection the other way around. So, our single file can still import a Widget (or any other type) and reference it without any warning/error.

- Rigid:

- For testing: it is difficult to perform a simple unit test without having code pollution ( _FakeRepository and testCompose()) And that’s a byproduct of our hard boundary. We may push toward having dependency injection, but this will defy the purpose of having everything in one file since we will break the hard boundary we set with the privacy mechanism. But if we can afford to have only integration tests, then that’s maybe fine. I tried to use the ‘library/part/part of’ keywords, but their functionality doesn’t seem to span the test folder — I couldn’t say for sure, since I couldn’t find any official documentation.

- For extensibility and reusability: If we have code or logic we want to share across features then we are obliged to have everything in the same file or else create a duplication — the logic is not part of a public API —.

I don’t favor this solution too much, for the different cons I mentioned above and I felt like fighting it in order to test it. and as I do TDD, I sometimes need the option to gear down and test logic in entities especially if it’s a complex logic (or logic that can create a combinatorial explosion if tested from a client class/code, etc.) But this is my opinion and different people have different takes , and there is always a trade-off between granularity and testability .

2. Package and Analyze :

This approach leverages the use of dart (or flutter) packages and dart static analyzer . And as we will see shortly it can be either an automated check or a compile-time enforcement.

The difference between dart and flutter packages is that the latter depends on flutter SDK and the former only depends on dart SDK. I tend to use dart packages whenever I have packages that don’t need any UI elements or types and only keep dependency from Flutter on the UI (usually, the main project) package.

The idea of this approach is to create the flutter project and create several other packages to encapsulate what we want to package together, for example in the case of a clean architecture we can have a package by layer, like a core package, an infrastructure layer, etc. In the case of a vertical slice architecture, we can package by feature or package by a set of cohesive features.

In our example, I have created a package called trivia_quiz that contains the logic and all the types related to getting a random question from Trivia API. The package also contains the related unit and contract tests.

You can find the example here .

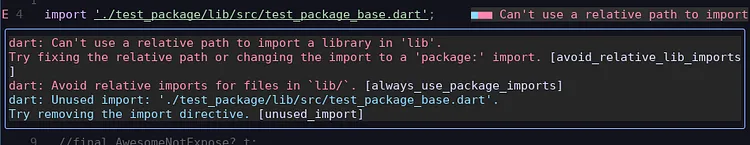

Alongside the package organization, we can use a dart analyzer to enforce the import style and only allow import statements referencing the package and not single files inside the packages with relative file imports. As you can see in the analysis_options.yaml I have marked the two analyzer’s hints to be errors, this way I have a stronger alert when they happen. I also needed to enable always_use_package_importssince it’s not enabled in the imported flutter.yaml file. unlike the avoid_relative_lib_imports.

include: package:flutter_lints/flutter.yaml

analyzer:

errors:

avoid_relative_lib_imports: error

always_use_package_imports: error

linter:

rules:

- always_use_package_imports

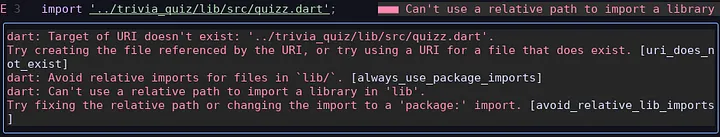

Now, if we have any dart-enabled IDE, or we run flutter analyze we can see the errors when we try to import something using a relative path, bypassing the public API of the package. (the documentation explains very well how the packages work, so I recommend reading it).

It’s also possible to integrate flutter analyze in your CI pipeline to gatekeep commits/PR from violating the aforementioned rules.

Where to create the package :

The behavior of this approach depends on where you put the packages you create:

- Inside the flutter’s lib folder: This will raise the linter errors mentioned earlier (the case of the previous screenshot) but doesn’t force you to import the package in flutter’s pubspec.yml.

- Outside the flutter’s lib folder: This will raise the linter errors mentioned as well as a compilation error and the project won’t compile at all, so you have a much stronger prevention from importing things you don’t want to import. And any package you need to use needs to be referenced in the pubspec.yml of the referencing package. The error triggered is the following :

Pros:

- Allow control of the public API: We can have as many files as we want in the package but we can pick which ones we want other packages to depend on using the export and show mechanism.

- Control package dependencies: Since each package has its pubspec.yaml we can control what each package depends on explicitly, and figuring out what the package uses is pretty easy.

- Easier to maintain and extend: Having a full package with the source code and the test together makes it nicer and easier to maintain. And we don’t worry much about what to put public and private (at least inside a package).

- Natural: compared to the single file solution, it feels more natural to work with packages to achieve enforcement.

Cons :

- Too many folders, too many files: The number of packages can create a complicated folder structure that can lead to difficulty in working on the project, especially when working on features that span multiple packages (but this depends on how we structure our packages).

- Relying only on the linter errors: Linter errors are fake errors, they don’t prevent the app from compiling, so enforcing this will need a CI that runs the analyzer and gatekeeps the commits that break the linter rules. But this depends on whether you choose the i or ii options above.

I favor this over the single file case and It’s my current way of working once the project starts to get a bigger codebase and a team starts growing. (really, when needed).

3. External packages:

The approaches we discussed so far are native to the language and the framework. Alongside that, We can add extra layers of enforcement using external packages:

1 — import_lint: this can be very practical in our use case since it provides lint rules to analyze imports in the codebase. From the README:

analyzer:

plugins:

- import_lint

import_lint:

rules:

use_case_rule:

target_file_path: "use_case/*_use_case.dart"

not_allow_imports: ["use_case/*_use_case.dart"]

exclude_imports: ["use_case/base_use_case.dart"]

repository_rule:

target_file_path: "repository/*_repository.dart"

not_allow_imports:

[

"use_case/*_use_case.dart",

"repository/*_repository.dart",

"space\ test/*.dart",

"repository/sub/**/*.dart",

]

exclude_imports: []

domain_rule:

target_file_path: "domain/**/*_entity.dart"

not_allow_imports: ["domain/*_entity.dart"]

exclude_imports: ["domain/base_entity.dart"]

package_rule:

target_file_path: "**/*.dart"

not_allow_imports: ["package:import_lint/import_lint.dart"]

exclude_imports: []

core_package_rule:

target_file_path: "package:core/**/*.dart"

not_allow_imports: ["package:module/**/*.dart"]

exclude_imports: []

This specifies which imports are not allowed not_allow_imports for the files that are included in the target path target_file_path. This package inherits what we said about the usage of the analyzer earlier but it offers more fine-grained control over the dependencies inside our codebase. The package looks maintained and it has 85% in popularity. I would use it if I needed it.

2 — dart_code_metrics: Although this is a general static analysis package, it provides a rule that may be of use to us, avoid-banned-imports and you can define the banned imports as follows :

dart_code_metrics:

rules:

- avoid-banned-imports:

entries:

- paths: ["some/folder/.*\.dart", "another/folder/.*\.dart"]

deny: ["package:flutter/material.dart"]

message: "Do not import Flutter Material Design library, we should not depend on it!"

- paths: ["core/.*\.dart"]

deny: ["package:flutter_bloc/flutter_bloc.dart"]

message: 'State management should be not used inside "core" folder.'

This package is also very popular and maintained, and it has other usages than only import banning. This can be of use if you already use this package in your projects and don’t want to depend on another static analysis package.

3 — dart_arch_test: This package provides a testing toolset that allows you to build automated tests to define the dependency rules in your codebase. Like :

import 'package:my_package/main.dart';

import 'package:arch_test/arch_test.dart';

void main() {

archTest(classes.that

.areInsideFolder('entity')

.should

.extendClass<BaseEntity>(),

);

}

Since this is an automated test, it can be integrated into the CI and it can be a strong indicator that we introduced a gap between our code and model. Unlike the first package, this one doesn’t look popular and it only targets Linux, macOS, and Windows (from what I can see in the pub.dev), and that’s a bummer for a flutter developer. And, looking at the repo I can see that there is a work in progress in some branches but not much activity.

Closing words :

I wrote this article to explore different techniques that a Flutter dev or a team can adopt to enforce an architecture in a codebase. Also I got frustrated about how easy it was to just depend on something with an import statement that probably the IDE added and not have any error or warning when we break a dependency rule (there is at least another person like me). This may or may not be the case for everyone, some people prefer doing code reviews in order to keep the codebase in shape, but these are not an alternative to that but tools we can use alongside it.

If you have read this far, then thank you, and let me know if I missed something or if you have achieved architecture enforcement in different ways.